Tags

Drama, Favourite movie, Fort Sedgewick, Graham Greene, Kevin Costner, Lakota Sioux, Literary adaptation, Mary McDonnell, Review, South Dakota, Western

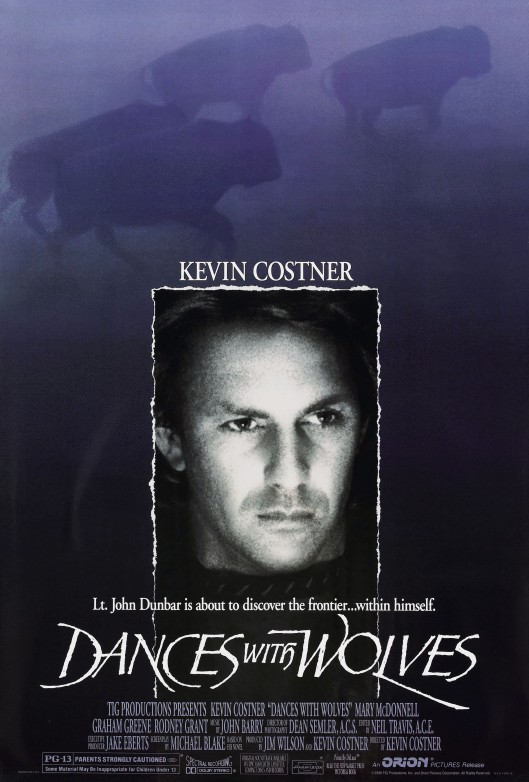

D: Kevin Costner / 234m

Cast: Kevin Costner, Mary McDonnell, Graham Greene, Rodney A. Grant, Floyd ‘Red Crow’ Westerman, Tantoo Cardinal, Robert Pastorelli, Charles Rocket, Maury Chaykin

After being wounded during a Civil War battle and receiving a citation for bravery, First Lieutenant John J. Dunbar (Costner) is offered his choice of posting in the Union Army. He chooses to be sent to the western frontier, and shortly after arrives at Fort Hays. There, he’s assigned to a remote outpost, Fort Sedgewick, but when he reaches it he finds it deserted. Electing to stay there anyway, Dunbar settles in despite the threat of marauding Indians in the area, and begins rebuiding and restocking the fort. Time passes and no other troops come to support him, but Dunbar is happy with the solitude, although his Sioux neighbours begin to take an interest in him. Deciding it would be a good idea to make contact with them, Dunbar sets off towards their camp. Along the way he encounters Stands With a Fist (McConnell), a white woman adopted when she was a child by the tribe’s medicine man, Kicking Bird (Greene). As he gets to learn more about them, Dunbar comes to understand and appreciate their way of life – so much so that when the Army finally arrives at Fort Sedgewick he sides with the Sioux against them…

Made at a time when the Western was in a moribund state, and clocking in at just over three hours on its original release, Dances With Wolves was the kind of production that had “risky” stamped all over it. It was Costner’s first time as a director and star, much of the dialogue was in Lakota Sioux which meant subtitles, and the pace – the opening sequence aside – was nothing if not languid. That it struck a chord with both critics and audiences alike was something of a miracle, and one that prompted the producers to release a Special Edition cut in cinemas in 1991. There will always be those who believe extended cuts are unnecessary, and often they’ll be right, but here the decision to add fifty-two minutes to an already hefty run-time isn’t as gratuitous or ill-advised as it is elsewhere. What the special edition does is to allow the audience to spend more time with the Lakota Sioux, and to discover more about their way of life, and why it proves so attractive to Dunbar. The movie, so attuned to the racial politics of the time, explores the Lakota Sioux community in much greater detail in this version, and the extra footage provides greater depth to many of the individual Lakota characters. Such immersion makes Dunbar’s decision to live with them all the more credible, and it creates a greater bond between the audience and the characters as well.

With its raison d’être thus established, the special edition needs no further defence for its existence, and so the movie can be enjoyed for its breathtaking South Dakota scenery, its elegiac feel, knowing sense of humour, gripping action sequences, and perhaps best of all, a beautifully textured and emotionally resonant score by John Barry. In assembling all this, and making it both visually arresting (thanks to DoP Dean Semler) and dramatically insightful, Costner has made a movie – and a Western at that – that manages to transcend its simple storyline and become a moving exploration of one man’s search for a meaningful place in the world. Dunbar’s journey is an heroic voyage of self-discovery, and Costner’s assured direction (working from a script by Michael Blake based on his novel), ensures that we go with him on his journey, our own curiosity piqued by where it might lead him. His relationship with Stands With a Fist, at once comical and earnest, awkward and tender, is enchanting and yet tinged with a sadness due to the nature of her placement with the tribe, and McDonnell’s feisty, layered performance is a joy to watch. The movie has come under fire for being yet another example of the white man as saviour trope, but this is to completely misread the narrative: what makes this distinctly different, and for its time quite innovative, is that it’s not Dunbar who saves the Lakota Sioux, but the Lakota Sioux who save Dunbar.

Rating: 9/10 – a triumph in every sense of the word, Dances With Wolves is a perfect example of a movie that takes its time in telling its story, and by doing so, proves more powerful and impressive than expected; entertaining and insightful, it’s also a movie that bears repeated viewings, as even in its extended form, there’s much that can be missed in a single viewing, and that’s without the pleasure of being reacquainted with such a great story and a great cast of characters.